Memories, Modernism and Our Concepts of a Misremembered Future

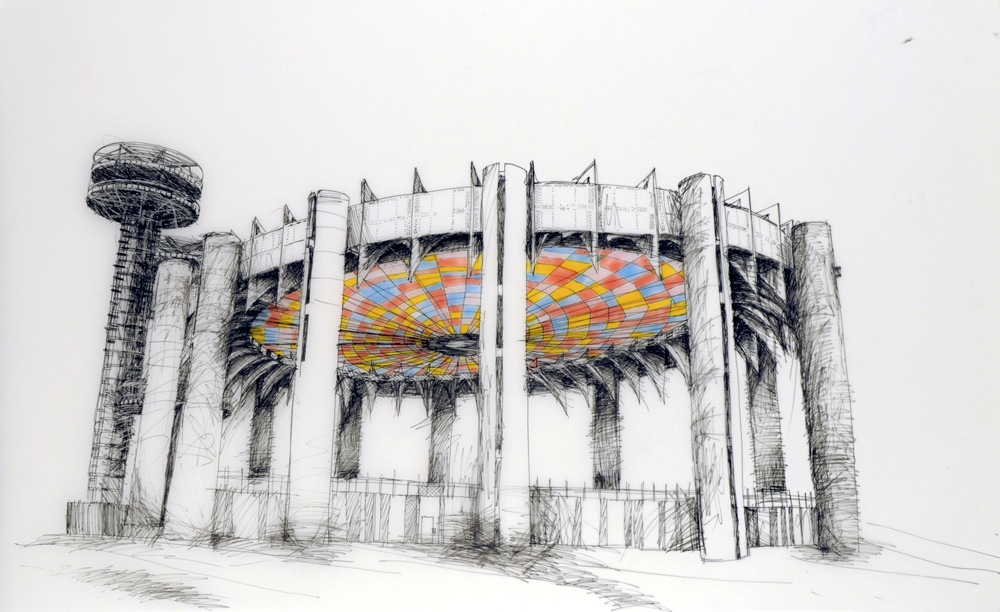

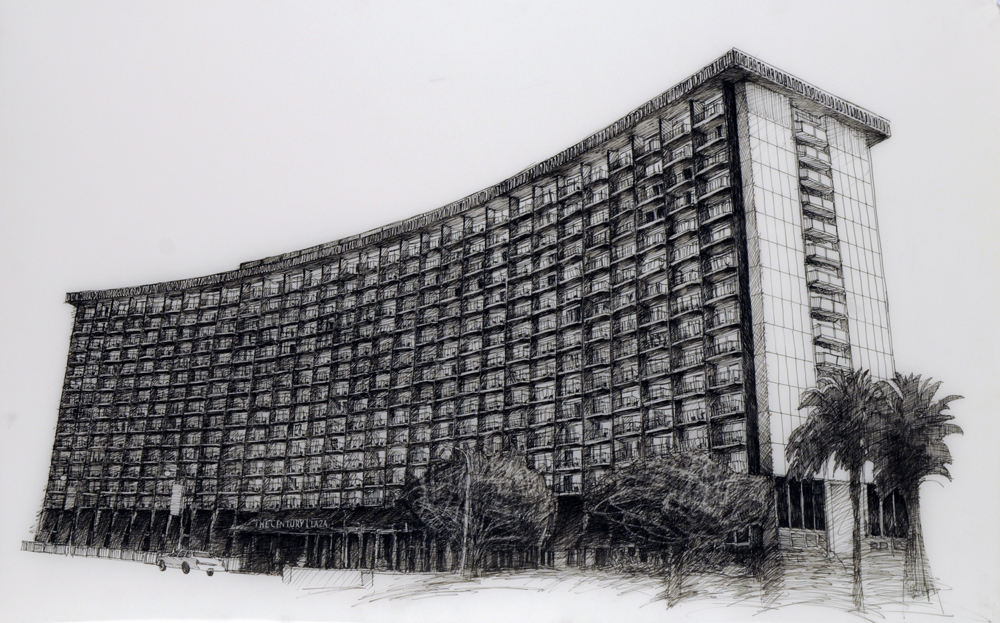

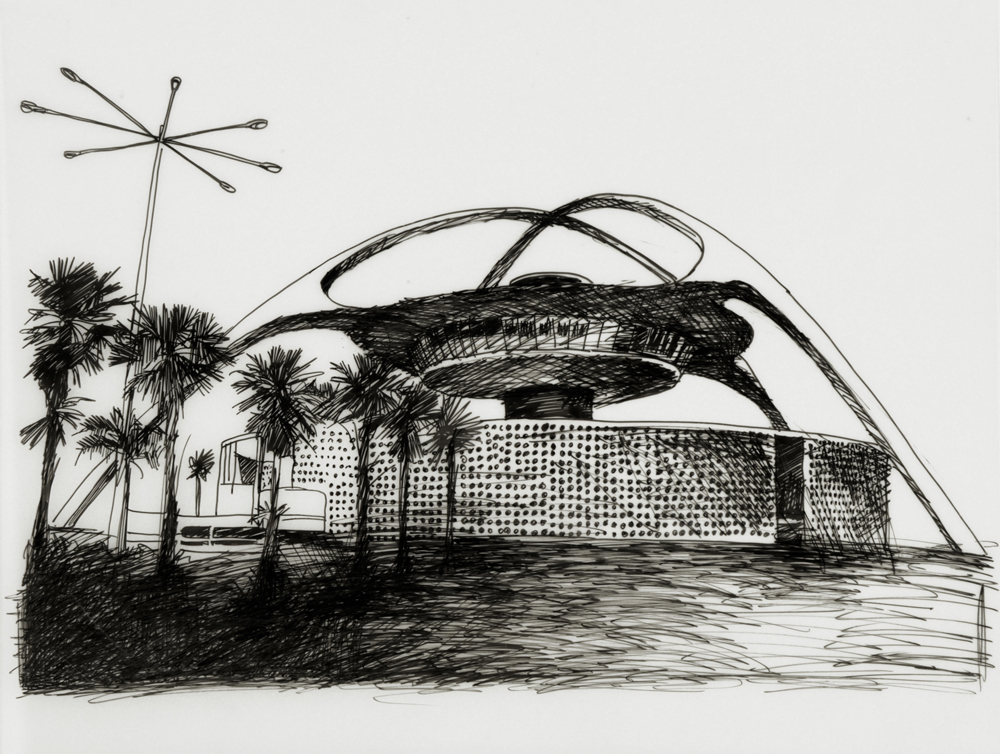

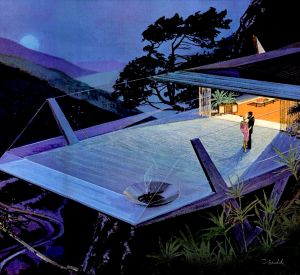

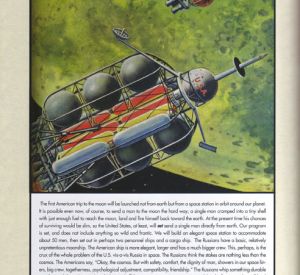

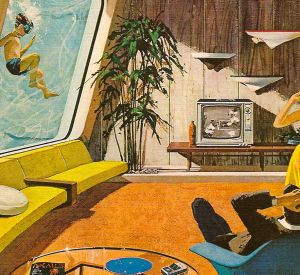

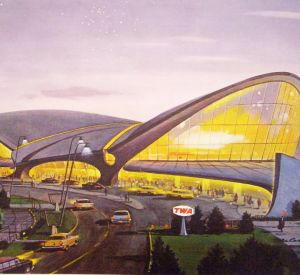

The recent exhibit of Deborah Aschheim’s drawings and architectural installations at Edward Cella A+A focused attention to the iconic modernist landmarks of Southern California that once represented the future. Aschheim’s works documented these structures, once the symbols of Southern California’s utopian dreams, which are now forlorn, crumbling commercial towers, buildings, and centers. Treated for the most part as “unacclaimed” monuments of a distant era, Ascheim described the buildings as a “visual gulf between then and now.”

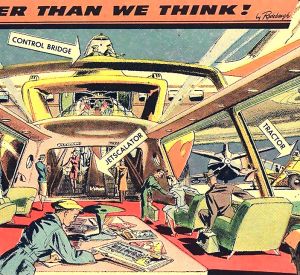

“When I was growing up, the future was a limitless possibility, jet-aged, space-aged, techno-utopia. ‘Modern’ meant new. Now, modern means old, and the future I grew up with seems dated, irresponsible, and obsolete,” claimed Aschheim.

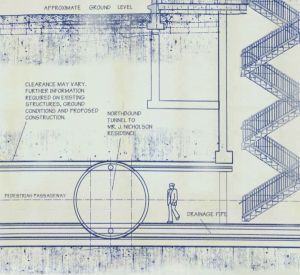

Aschheim made several visits to each site, and she created her unique works over time. Aschheim explained, “I have been urgently seeking out the buildings, flying and driving and taking trains to them before they are erased. I don’t want to go inside the buildings. I circle them, trying to understand them before they are removed or renovated into the present. It is a strange way to feel about architecture. I am drawing them and building them, somewhat inaccurately and not to scale, entombed in imaginary scaffolding. I am the same age as the buildings. It is a kind of self-portrait.”

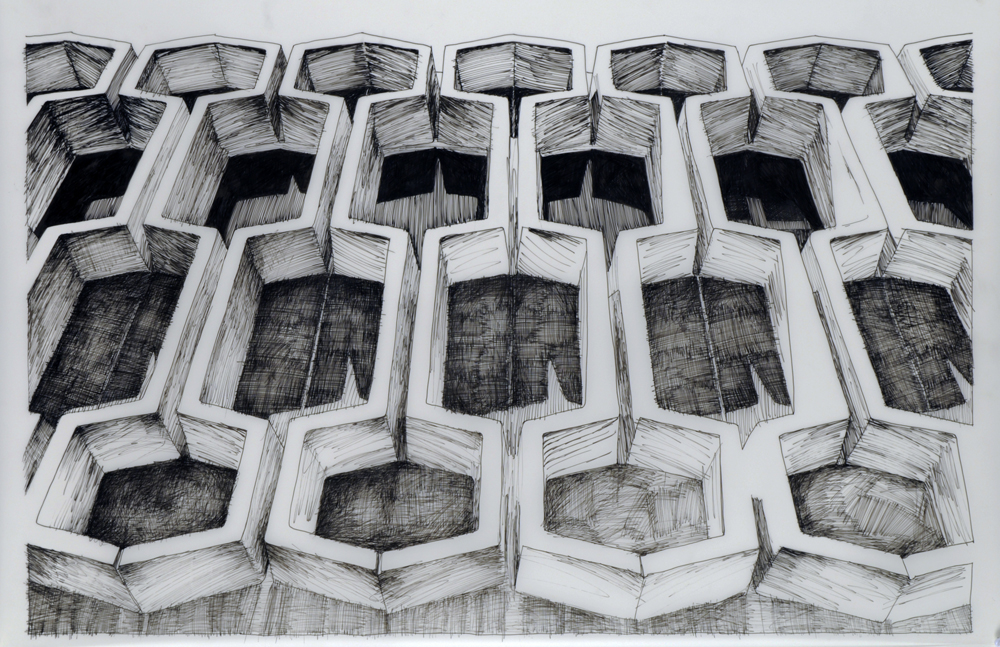

Aschheim played the role of interventionist who tried to conceal the original forms of the buildings with scaffolding. The concealment ultimately became a representation—not of an old memory of the original buildings—but a process meant to create a new memory of the original buildings. She argued that this evolution created a new memory of an “old future.” Asked how the erasure and concealment of the original forms fit into her strategy of creating “old futures,” Aschheim posited:

The scaffolding was a strategy for making crisis, displacement, the pixilation of time and space, and the ghostliness of the hardscape world visible. When I used my scaffolding, I tried to conceal and create transparency that itself erased at the same time. When I moved through the cities, scaffolding made me remember the second law of thermodynamics—that everything always fell apart. Scaffolding appeared to be a temporary support for some work in progress, but the buildings were never finished, and the scaffolding never went away. The scaffolding was like the physical embodiment of the mutability of everything, the fictitious nature of the past and the future, the mutability of memory itself. It was the barnacles on the pier, or kudzu, amyloid protein that accumulated in your brain, digital files piled up on your hard drive. I could describe it better if I weren’t so afflicted with it.

Aschheim recently began working with Lisa Mezzacappa, who created the soundtrack to Nostalgia for the Future. The soundtrack combined processed, edited, and reconstructed recordings of Mezzacappa’s chamber ensemble Nightshade, who performed live. The soundtrack also included various analog sound sources, like rotary telephones, cassette players, and typewriters. Like the iconic buildings and structures of Aschheim’s work, the tactile, textured voices and objects heard in the soundtrack have rapidly disappeared from our daily soundscape.

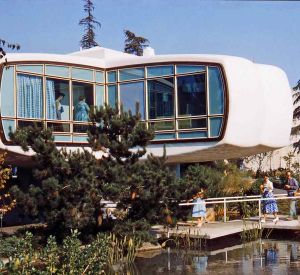

Aschheim’s work really affected me as I looked at the different drawings and sculptures of the familiar buildings in the Los Angeles area. They brought back the memories of when I grew up there and regularly saw all those great structures. I thought of Tomorrowland, and I also thought about what the future held. Every time I return to visited L.A., I think about these buildings, and I seek them out. I want to see them again to have them remain a part of my landscape, my history. I want to be part of them, as I try to do with Encounters. I go there out of respect, and because I wonder if the same scene would be there the next time I visited.

When I look back and think about the landscape of L.A., those buildings stand out to me. It isn’t the same building after building after building you see as you drive down the street; it wis these particular buildings and their unique architecture that stand out. And it’s up to you to imagine and create your own architecture, what it means to you, and what it represents. Although it is impossible to recall every little detail, you know they are there, that they are icons, and everything else somehow fades into the background. I think that being an Angeleno means that you probably take them for granted, but you still need to have respect for them. You never want them demolished. I appreciate what an artist like Aschheim has done to memorize the original buildings, how she memorialized them, and how she documented them. That meant a lot—not just to somebody like me who was originally from area—but because she seemed to respect the things we want to keep around. How do the buildings and their associated landscape affect us? Why do we want to keep them around? Could it be because they originally represented a new style or a possible future when they were first built? People have to make their own conclusions about that. We all have our own reasons to want to keep something, to have it to remain.

I recently thought of an interesting comparison to a current “crisis:” A group is trying to tear-down/move the Tonga Room in San Francisco. Preservationists and particularly San Franciscans (not all of whom are Tikiphiles) are outraged about it. A reporter even had the audacity to ask, “Who cares? It just something of the past, something obsolete, something nobody cares about.” The outcry to that is, “Outrageous!” I was truly shocked by the reporter’s statement. But it’s really the same idea that these things affect people…buildings and places and memories, and the perspective you have on them. Individuals’ perspectives are affected when someone says, “Hey – we’re getting rid of this!” It’s very interesting to me how architecture and places and memories are so completely intertwined into the landscapes of our lives.

And as I watch things crumble before my eyes and do not have an answer of what to do about it, at the very least I can say “thank you” to Deborah Aschheim for creating this body of work.