The Best of Everything – The Original Sex & The City

A publishing house typing pool is the seething heart of the aspirations of a cadre of working girls, marking time until they marry Mr. Right and settle down. Caroline Bender (Lange) battles her career aspirations and fear that she will morph into scary book editor Joan Crawford. It’s the original Sex in the City.

Rona Jaffe’s novel, The Best of Everything, is about four girls (and their friends). The author’s stand-in is the ambitious Caroline, who is pining for her overseas fiancé. She shares an apartment with April, who sleeps with her dream man expecting marriage and Gregg, an aspiring actress whose rejection by a noted playwrite turns her into a deranged stalker. In the book, there is a fourth, Barbara, divorced after a year of marriage and raising a small child. All these girls feel the pressure of society’s expectations, which say they must start to panic, at around 23, if they aren’t married. They want freedom, but only a taste of it, before they settle for domesticity.

A perfect continuation of Peyton Place, with Hope Lange (Oscar nominated for her role in that previous 20th Century Fox racy soap opera) arriving in New York City, after no doubt escaping from some other backwater. She quickly makes friends with the other girls, so like herself in their plans for marriage (Caroline is engaged) and so unlike her, since she hides a secret ambition to be a reader, and then an editor. College graduates, they all define themselves only in a relationship with a man. The author, herself, never married, choosing to avoid, “the rat race to the altar” (NY Times obit).

Here’s to men… bless their clean cut faces and dirty little minds!

Jaffee had a well to do upbringing on the Upper East Side of New York. Graduated from Radcliffe, she worked her way up from file clerk to associate editor at Fawcett Publications when this, her first novel was published. It’s no surprise that she soon became a regular contributor to Cosmopolitan, in the Sex and the Single Girl days of Helen Gurley Brown. It was expressly designed to be both the urban answer to Peyton Place and to a previous era’s working girl melodrama, Kitty Foyle. A friend of Jaffe’s overheard that movie producer Jerry Wald was searching for a modern Kitty Foyle to option for a movie, and told him that she knew someone who was writing a novel that might fit the bill. Jaffe quizzed 50 other working women to confirm that they shared the same basic experiences that she and her friends had. Jaffe suspected her book would be a success when the Simon and Schuster typing pool begged her to fill them in on what happened next. The book was edited by Robert Gottleib, who would go on to edit Joseph Heller’s Catch 22 and The New Yorker. It took only two weeks to appear on the NY Times Best Seller list, and the novel stayed there for five months.

Jaffe said in an interview on NPR that although the book certainly reflected her experiences, she always knew she wanted to be a writer, and took a job in publishing to find out how to get published. She said the 1950s were so hypocritical, and many young women reading her book felt as if they were the only sinner having an affair and were relieved to find out that they were not alone.

Jaffee was involved “every step of the way” in the film version of her novel. She insisted to the director that it must be “real, real, real.” She supervised the sets, the costumes and the way the actresses behaved. She remembered The Great Virgin Conference, where executives decided which girls should be virgins and which not, never mind what was in the book (Jacobs).

The film was set in the sparkly new Seagram Building at 375 Park Avenue, between 52nd and 53rd. The philosophy of the International Style of architecture was that the clean lines would extend from the cool exterior, to the lobby, elevators and then the vast office floors. “Everything offers a sense of bright, rational possibility, miles removed from the hurrying crowds and Art Deco urgency of earlier skyscrapers (Saunders 133). She enters the lobby, and then there is a cut, as the office environment itself is a Fox Studio interior.

The offices reproduced the interiors of Pocket Books, the paperback publishers of The Best of Everything. The rectangular design is faithful to real life office environments, except with the explosion of Technicolor. Manhattan offices were typically glass, transparent and translucent, white, beige and natural wood, with metal accents. In the hands of Fox art directors Lyle Wheeler R. Wheeler, Mark-Lee Kirk and Jack Martin Smith, it becomes “a Mondrian you could live in, ‘Broadway Boogie Woogie’ in coral, mustard and French blue. The Fabian desk lamps, they’re like Balenciaga hats. The cramped apartment of editor Amanda Farrow (her chandelier hangs at a mesmerizing shoulder height) and theater director David Wilder Savage (books, books and African art) are two versions of Michael Greer midcentury chic” (Jacobs). As in The Apartment, there is a great contrast between the décor of the workaday world, and the home. Each flat summarizes the personality of the inhabitants. It’s quite clear that these offices form a major influence in Amy Wells’ set designs for Mad Men.

As stated in the reissued novel’s jacket blurb by Julie Burchill: “It harks back to a saner time, when choosing progress and modernity was as straightforward as ordering dinner – ‘Two scotches with water on the side, and two steaks’.” (Guardian)

Surprisingly racy, one of the book’s most interesting relationships is between Caroline and the heavy drinking Mike who is 20 years older than she is. A modern reader can’t help but wonder if he is a deeply closeted gay man. They have some pretty frank conversations:

“Would you like to sleep with him?” Mike asked, calmly and curiously.

“Mike! I don’t think about the men I meet that way.”

“Why not?”

“Well, girls don’t”

“Of course they do,” Mike said finishing what was his eighth or ninth drink. “Women have exactly the same feelings as men do, if they’d only admit it to themselves. A man sees a beautiful girl walking down the street, or he meets her somewhere, and he says to himself, matter-of-factly, with no intention of doing anything about it, I’d like to sleep with that girl. That’ doesn’t mean he’d even try to start a conversation. But he accepts his own feelings.” (p.93).

He tries to talk her into having phone sex with him (is this not a first?) and then, eventually, they go to bed together, once, and, if I understand the veiled language correctly, they have intercourse, but not to the point where she would lose her virginity, since society perceives this as her sole marketable commodity.

April is holding out thinking her rich boyfriend won’t marry her otherwise.

“That’s why I hate going to be with a virgin” Dexter said firmly. “They think they’re giving you the greatest thing they have to give in their whole lives. What are they giving you? It hurts them, they don’t know one thing about how to conduct themselves in the sack…the whole procedure is a pain in the ass for the guy. If I know a girl is a virgin, I wont even make a pass at her.”

“Well, I’m a virgin” April said indignantly.

He reached over and took her hand. “That’s different,” he said, half in humor. “I love you, so I’m willing to put up with the inconvenience.” (147)

Of course, this will end up with a Saturday date at the back alley abortionist. In one of the novel’s most powerful scenes, she carefully arranges her desk on Friday afternoon, since there is a good chance she will die during the procedure. She wants to make sure that everything is in order, so the girl who sits at her desk on Monday can take up her typing where she left off. Of course, just as the word “rape” was not used in the film of Peyton Place, the word “abortion” was not used in the film of The Best of Everything. Diane Baker’s character would never consider one, but luckily nature takes its course and Baker says a line that Jaffe thought “stupid” “I’m so ashamed. Now I’m just somebody’s who’s had an affair” a line of self hatred that resonates with many gay fans of this film.

Caroline debates whether to having a fling with a well-known womanizer, “Girls always think, ‘I am going to be the exception’” Caroline thought; it’s a weakness of the species, like a collie’s tiny brain.” (336).

Jaffee wanted Suzy Parker to play Gregg, and asked her personally to do the part. Parker was the biggest supermodel of the day, and at one time was thought to be a likely movie star, although it never quite happened for her. Hope Lange had just gotten an Oscar nomination for Peyton Place and Diane Baker had gotten good reviews as Anne Frank’s older sister in Diary of Anne Frank. They were both contract players, a bargain for Fox. Their careers unfortunately never lived up to the promise the studio saw in them.

Baker said of working with her on-screen roommates Lange and Parker, “those scenes with the three of us were fun scenes to play. Suzy Parker was very funny, and we all laughed. Hope was great. Working with all of the girls, and in that atmosphere, it took a lot of the strain off of you” (Jacobs).

The strain she referred to was Joan Crawford. She consented to do the part because her husband had just died and she hoped work would take her mind off her troubles. It had been her happiest marriage, and she was in financial difficulties. A bottle of 140 proof vodka was her constant companion, shocking some of the younger actresses. Jerry Wald had helped her get Mildred Pierce, and she trusted him when she took this, her first supporting role. Crawford was 55, and the undeniable star of the film, although her part is small. She arrived in a limousine with her entourage, and no one could speak to her unless spoken to first. She also insisted on keeping the set very cold, which made everyone ill, perhaps to preserve her heavy make-up. It was a career comedown, and she was emotionally vulnerable. It did not help that she perceived herself in competition both with the actress with the biggest part, Hope Lange, and the beautiful Suzy Parker.

“Films like Peyton Place (1957), The Best of Everything (1959) and A Summer Place (1959) often exposed the pressures and resentments that were building up in the collective unconscious of American women—before clamping the lid back down on the pot and claiming everything was fine” (Benshoff, Griffen 224)

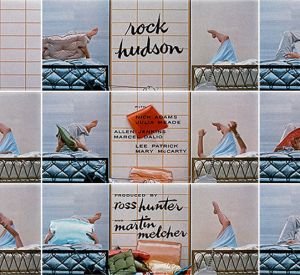

The film was supposed to be naughty, and it was, for its day. There were lavish magazine promotions and in major markets there was a “Miss Best of Everything Secretary” contest. The winner got a line in the movie. “Oh, Caroline” she says to Hope Lange, who replies, “Not now, later, Dinah,” an insert clearly shot and interpolated later. There was a splashy New York premiere at the Paramount Theatre on Broadway. The reviews were pretty good, although many males critics dismissed the film, like Time magazine as “cautiously diluted Scotch-and-Sodom”

To a modern viewer, it’s remarkable how the men in the film are all pills, lechers or worse, and that there are no happy endings. Either your doctor boyfriend brings his socks for you to darn to a date, or a girl has a career and is sad, being forced to choose between no man or a married one (since she lacks that critical sock darning gene). The gorgeous Cinemascope print from the Fox Archive (thank you Caitlin Robertson and Brian Block) kept the audience enthralled. Bob Evans was hissed for his skullduggery, and the applause at the end was enthusiastic and prolonged.

Like much popular fiction, once its moment was past, The Best of Everything went out of print. But, the novel was republished, when Mad Men’s Don Draper was seen reading the book in bed, the better to understand the girls in the office.

“Woman’s picture!” said Jaffee. They said to me, ‘Do you mind that you’re known for writing women’s books?’ I said, ‘Why because women write about stupid things like relationships, and men write about really important things like killing?’ You know, that was their attitude” (Jacobs). Some things never change.

Written by: Laura Boyes. Republished with permission.

Sources include: The Best of Everything by Rona Jaffee, Rona Jaffee’s NY Times obituary, Wikipedia, The Guardian, NPR America on Fim: Representing Race, Class, Gender and Sexuality at the Movies by Harry M. Benshoff and Sean Griffen, Vanity Fair’s Tales of Hollywood edited by Graydon Carter: “The Lipstick Jungle” by Laura Jacobs p 105-126 from Vanity Fair March 2004, Celluloid Skyline by James Saunders, Films in Review, November 1959.